Navigation and Chart work - Passage Planning

Preparation

Before you start to plan any passage, there are certain factors that should be considered, they can be broken in to two areas:

(1) Crew considerations.

(2) The boat and its equipment.

Crew considerations

The weakest link in any passage is frequently the crew. A safe skipper will consider the following points in relation to the crew and expected voyage.

• Their experience.

Ideally, the experience and skills should be spread widely amongst the crew. Many yachts are run so that the skipper is the only one on board who really knows what is happening and how to deal with all the complicated jobs aboard, such as navigation, VHF radio use, and boat handling under power. In this case, if the skipper is disabled, the crew has little knowledge to draw on to bring the boat to port safely.

One of the aims of the skipper must be to train and trust the crew to perform all the tasks that the skipper can. Obviously, this will take time but any opportunity to pass on skills and knowledge should not be missed. You may think that if the crew can do the tasks the skipper has been doing, that there is nothing left for the skipper to do, this is not the case, the skipper will find that he is able to work at a higher level, and plan further ahead.

I always think that the best skippers are those who do not appear to do anything-but the boat runs smoothly and nothing goes wrong. This only happens when the crew is well trained and the skipper is planning ahead!

• Health.

Consider the health of the crew before any passage. If you are undertaking a long voyage that will be some days from medical assistance, this could be vital. However, the stresses of sailing, especially in rough weather could also trigger problems for anyone suffering from a heart condition, diabetes or epilepsy.

• Seasickness.

If a crew is prone to seasickness they may become a liability in rough weather and just add to the skipper's workload. This does not mean that you should not take them to sea, it just requires some prior thought.

Factors that increase the risk of seasickness are:

• Sailing in the open sea early in a cruise.

• Rough weather.

• Sailing to windward or straight down wind.

• Long passages (people are rarely sick if at sea for only 2 hours).

• Working on the foredeck.

• Going below (cooking, navigating or using the heads).

• Eating and drinking too much the night before.

• Stress.

• Diesel or other smells below.

A prudent skipper will consider the passage plan in the light of these factors and modify it as appropriate for the crew.

• Crew desires and expectations.

To run a happy ship it is a good idea to ask the crew what they expect and would like to do, people's expectations vary a huge amount! Some people are happy changing a headsail on the foredeck in a force 7, others idea of a good cruise, is a trip to as many public houses as possible!

• Crew compatibility.

On a small boat in bad weather conflicts between crewmembers can ruin a cruise. Try to find a crew where everyone is able to work together.

The boat and its equipment

The following factors should be considered when planning a passage:

• Suitability of the craft.

Not all vessels are suitable for all passages; the skipper must consider the size and type of boat.

• State of maintenance.

Sailing a vessel that has been poorly cared for can be very stressful as well as dangerous. Frequently, one small fault leads to another until a major problem has developed.

• Consumable supplies.

Are adequate supplies aboard and where can they be replenished? This list includes: Food, water, fuel and gas for cooking.

On a power driven vessel, or if there is little wind, the skipper must have a good idea of the fuel consumption and likely range at different speeds and conditions.

• Equipment.

Does the vessel have suitable equipment aboard?

• Safety equipment.

• Tools.

• Navigation, charts, pilots, almanac etc.

• Domestic equipment.

Detailed planning

Planning a passage should start with some basic research, after all, there is no point in planning a voyage, and only to discover that you can not enter the harbour you planned to visit because it is too shallow!

This research should cover the following basic points:

(1) Is the weather suitable?

(2) Are there any restrictions on leaving the homeport?

(3) Are there any restrictions on entering the port of destination?

(4) Are there any restrictions on route (shallows or hazards)?

(5) When will the tide be in our favour?

Weather

The weather forecasts must be studied for several days before the voyage begins, it is not enough to turn up on the first day and get the current forecast. If you do this, you will not have a feel for how the patterns are moving through.

Specifically, we are looking at:

• Safety.

Is it safe to make the planned passage in the forecast conditions?

• Boat speed.

Wind force will obviously influence boat speed, especially in a sailing vessel, but the direction will also make a big difference to speed and comfort.

In a power driven vessel, the wind over tide conditions may become a major factor in planning. A high speed planing craft will travel at perhaps 30 knots when the wind and tide are together but only 10 knots when they are opposed.

• Visibility.

Will the visibility be suitable to make the passage? Factors which will reduce the visibility are, fog and mist, heavy rain, snow and even sand storms!

• Comfort.

How comfortable will the passage be? When people attend sailing courses at a school they will be sailing in virtually any conditions. If you are on holiday, you or your crew may not wish to sail when conditions are unpleasant.

I recently sailed a boat to Northern Spain from the South Coast of the UK for a Yachtmaster Ocean course. The passage was to windward in winds from force 5 to 8, and whist it was good experience for the students. It could not be described as enjoyable!

A few days after we arrived in Spain, many other British vessels began to arrive, they had waited then left after the wind had changed direction, and had a very pleasant crossing. If you are on a long cruise, it may pay to wait for the right weather to start.

Departure restrictions

There is no point in planning a passage if you can not leave port when you need to. Restrictions may be caused by:

• Lock gate operating times, not all locks are 24 hours.

• Entrance too shallow, many harbours have a bar or are closed by a sill. See page 85 of the Training Almanac, S. Kilda.

• Will the tide rise sufficiently? Some harbours are not accessible at neap tides.

• Ferry traffic may delay departure. In busy harbour like Calais or Dover, it may be necessary to wait over an hour to be given a departure slot, as there is so much commercial traffic.

• Some harbours are not accessible in the dark, as they are unlit.

Arrival restrictions

Any of the above may apply.

Passage restrictions

Is the passage in deep water or are there any areas that we must pass through with sufficient rise of tide?

Are there any sections that can only be crossed in daylight?

Tidal streams

When do you need to leave to make optimum use of the tides? On a short trip, it should be possible to make the entire passage with the tide. However, on longer trips it may be necessary to sail against the tide, it makes sense to do so in places where the tide will be weakest.

The tide will be weakest in bays and strongest off headlands. In an area of very strong tidal streams, such as a passage from Cherbourg to St Malo, it may be necessary to anchor for a few hours in a bay off Sark and wait out a foul tide.

Where to start?

No two passages are the same and only experience will tell you which information is required before setting off. Obviously, having a suitable weather forecast is of primary importance, and this is the first place to start your planning.

Once you have decided that the weather is going to be suitable for the passage that you wish to make, the next step will always revolve around tidal information. The important factor is the tidal gates.

A tidal gate, is a tidal element that has to be passed through between certain times: They are either related to the tide height or flow.

• An example of a gate caused by a tidal height, would be the bar at the entrance to Namley harbour (page 52).

We have already dealt with this in the pilotage sections, and when calculating tidal heights.

• A gate caused by the tide flow, is the period when the tide is flowing in the required direction.

To find the period of favourable tide we normally use the tidal stream atlas, filling it in with the times of the tides for the whole day.

If we wish to make a passage from Dunbarton to Victoria on 6th April in daylight, we would start by looking up the tidal information for Victoria for that day.

6th April

Victoria Summer Time

HW 0627 4.4

LW 1300 2.0

HW 1944 4.2

Range = 2.4m therefore a neap tide.

High water in the morning is 0627 Summer Time, so on the diagram for HW Victoria, on page 19 of the Training Almanac, we would write, 0557 to 0657.

This period covers the hour from half an hour before to half and hour after high water Victoria.

We then need to fill in the diagrams for the hours before with the correct times, then do the same for the times after HW Victoria.

By observation, the tide first starts to run from Dunbarton towards Victoria, 1.5 hours after HW, or 0757. Therefore, the earliest the tide would be in our favour is 0757 Summer Time. Allowing for half an hour to clear the harbour, stow ropes etc this gives a start time of 0730.

The latest the tide is in our favour is 6.5 hours after HW, or 1257. Therefore, the latest time to arrive at Victoria is 1257 Summer Time.

Our tide gate is 0757 to 1257.

As the passage is about 35 miles, this means that a ground speed of 7kn must be maintained to make the passage. It is likely that the vessel will be going against the tide at the end of the passage but there is still plenty of day light left.

Preparation time

An important factor to allow for is the time it takes to get from your mooring to outside the harbour and sailing. Even in a small harbour it will take about half an hour to clear the harbour, in a large harbour like Falmouth it may take an hour as the moorings are some distance from the entrance.

If the time available to make the passage leaves little room for delay, this preparation time must be allowed for. A similar period may be required at the destination!

In the morning, at a normal rate of activity, allowing for boat checks, breakfast and visits to the ablutions, most crews will take between 1 1 / 2 and 2 hours to go from their bunks to sailing. Alternatively, most crews can be up and ready in 10 minutes, if everything is prepared and breakfast is eaten underway!

Daylight

For this passage I would probably choose to catch the tide at 0800, this would require casting off the mooring at 0730, at the latest, so it should be light.

Entering a harbour in the dark is probably the hardest part of skippering a boat, even more so if it is one with which you are not familiar. A factor to consider is whether it is better to leave a harbour in the dark, then arrive in daylight. If the destination is particularly difficult, this may be the deciding factor.

In an area where there are no lit marks and numerous hazards or for anyone with little experience (basic Dayskipper level), the hours of daylight should be considered to be the limits of passage making.

The skipper should always know how long the tide gate will be open, and constantly checking the vessel's progress against the distance and time remaining.

It is very unusual for a passage to proceed as planned, if you are not going to make the next tidal gate you must know in plenty of time. This allows the skipper to decide:

• To carry on, but arrive much later than first planned.

• To speed up the boat (sail change or engine).

• To change the destination.

Not making the tidal gate must never be a surprise!

Ground track and distances.

The next step is to draw on the chart the required ground track. As this is done, we need to look for any navigation aids, that may help and for any hazards on or near the route we plan to take.

For a daylight passage from Dunbarton to Victoria, we will start from the marina, the pilotage out to Synka Sound should be fairly simple.

Once in the sound, a course of 175°M for 2M should see the vessel in clear water.

The next hazard is fairly serious, the Cohen and Robinson Rocks lie on our route. We need clearing lines to ensure we stay in safe water. Stayingoutside the 50m contour line is one option. Clearing bearings on the south east corner of Swifta Island (46°10'5'N 005°55.5'W) and the CG station on Cape Woodward will also help. A course over the ground of 265°M for about 6 miles will clear Robinson Rock.

The next course is about 335°M for 17.5 miles to a point off the port hand buoy off West Point. The main hazard are the rocks off S. Anthony's Head. These can be avoided by keeping outside the 30m contour and using clearing lines on Tindall Point and S. Anthony's Head.

A course of 045°M for 6 miles will take the vessel to the harbour entrance.

The rest of the passage is pilotage to the anchorage or marina.

Course to steer to allow for the tide

These tracks are over the ground; we then need to consider if we need to work out a course to steer to allow for the tide. If a course to steer calculation is required, we only do the first leg of the passage, the others should be calculated just before they are required. In this way, the information for boat speed and tide will be as accurate as possible.

For most of this passage a course to steer calculation is not required, the exception if the leg past the Cohen and Robinson Rocks where the tide will be setting the vessel towards the danger.

We may also choose to place a waypoint in the GPS for each of these turning points and run them together as a route, this would make this passage very simple!

Clearing lines

At this stage, it would be prudent to put some clearing lines on the chart to ensure we clear the rocks.

These clearing lines are our back up system; they act as a check to our course steered.

Aids to navigation

We may also think about what we will see that may help us fix our position. In an unfamiliar area we may not see these marks but it is useful to have some prepared.

We may see:

CG station at Cape Woodward.

Flagstaff at Tyndal Point.

S. Anthony's Head lighthouse.

Radio Mast at Hill Head.

Red buoy and light house at West Point.

Very tall radio mast behind Victoria harbour.

Hazards on route

• Cohen Rock.

• Robinson Rock

• Skerries Bank.

• Bramble Rocks.

• Overfalls at West Point ledge (neap tide and probably slack when we arrive)

Pilotage plan

We now need a pilotage plan for leaving harbour and arrival. It is easy to forget that getting out of a harbour can be just as difficult as arriving. Remember that it will look completely different going out.

If possible it as a good idea to have a look outside the harbour so that you have a good picture of where you will be heading in the first few minutes. The start and end of passages are often the most difficult, equipment is being stowed, sails going up, there is lots of traffic and usually there is limited space to manoeuvre.

Recording the plan

A clear record of all this information needs to be kept where it will not get lost. Writing it on the blank pages of the logbook is one approach, another that works well, is to have a hardback notebook to keep details of passage plans.

Cross channel passages

When we sail longer distances we start to encounter different problems.

• Cross channel tides.

The first cross channel voyage for many people is from The Solent to Cherbourg. This is a good choice because the arrival is straight forwards and the facilities good once you are in harbour.

The special factor with this trip is that the distance is 60M from the Needles to Cherbourg, at an average speed of 5kn, the passage will take 12 hours.

In theory, a 12-hour passage means that the tides cancel out. In practice, the tides on the French side are always the strongest, and so an offset has to be allowed for.

We normally do this by calculating the total east and west going tides, subtract one from the other, and the resultant is the distance we will be offset.

Hour West tide. East tide.

1st 0.5M West

2nd 1.2M West

3rd 2.5M West

4th 2.6M West

5th 1.3M West

6th 0.4M West

7th 1.0M East

8th 2.1M East

9th 3.2M East

10th 3.0M East

11th 2.8M East

12th 1.0M East

Totals 8.5M West 13.1M East

Result 13.1-8.5= 4.6M to the east.

We could work out a course to steer for an offset of 4.6M. In practice this is quite difficult, the triangle would be 60M on one side and only 4.6 on the other, difficult on the average chart!

One approach is to draw it on an Admiralty tidal stream atlas; it works because they are to scale.

An easier method relies on the fact that a course change of 1° over a 60M distance changes the position of the end point 1 Mile. So if we measure the Track as being 180°M, for a tidal offset of 4.6M, we could steer 185°M and this would allow for the tide!

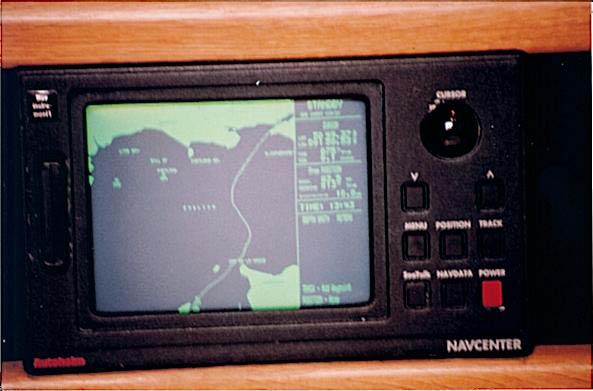

The image below is of a track on a chart plotter for a voyage from the Needles on the west end of the Isle of Wight to St Peter Port in Guernsey. During the voyage the vessel remained on the same course through the water from start to finish, the curves on the screen show the resulting track over the ground caused by the tidal flow.

Aiming off

As it is difficult to be certain how long a passage will take it is prudent to aim off to one side of the destination. The two factors to allow for are:

• The tide.

• The wind.

Ideally, we want to be up tide and upwind of the destination, then as we get closer and the ETA is more predictable, to close in towards it, using the wind and tide to carry us to it.

If the wind and tide are contrary, it is often better to be up tide, and sail against the wind for a short distance. The skipper would have to judge this for each situation.

Beating

Planning for an upwind leg is very difficult, especially in regard to how long it will take. As you gain experience with a particular boat, it becomes easier.

With novice crews I usually double the distance to the destination, with experienced helmsmen adding 50% is usually sufficient.

Lee bowing the tide

A concept that is useful to know about, is that of lee bowing the tide.

This means that if you are beating across the Channel you arrange to tack at the turn of the tide. The intention being, to have the tide on the lee side of the vessel.

This decreases the angle between tacks and improves the apparent wind.

If this is done it will reduce the crossing time to the minimum possible.

In practice, it can be very hard to arrange for this to happen exactly as described, but it is a factor that an experienced skipper should consider.

Bolt holes

Any voyage may need to be cut short for a variety of reasons ranging from, the boat going too slowly to make the passage in the allotted time, to some sort of disaster or injury to the crew.

With this in mind part of the plan should be to consider what the options would be if a change of plan is required. The skipper must have this information available to assist with making changes to the plan. If this aspect is forgotten, it will be very difficult to make the best decision in an emergency.

Factors to consider are:

• The accessibility of the harbour. Are there tidal restrictions and does it have an all weather entrance? Cherbourg is a good example of a harbour with 24-hour access. It can be entered no matter how bad the conditions.

• The facilities available. If you need some emergency repairs, will suitable services be easily accessible? If you were cruising in the Channel Islands and needed some repairs, St Peter Port would be better than St Malo for a British vessel because all services are available; they speak English and if necessary the crew can take the ferry home.

Part of the passage plan should be to prepare a pilotage plan for any boltholes on the way.

It may be that the only boltholes are the port from which the vessel departed, or the destination. If a boat is sailing from Alderney to Cherbourg , the only sensible options are to return or carry on. If the vessel had travelled more than a few miles, the only option would be to continue, because it would not be able to return against the tide!

Forecasts

When you travel to an unfamiliar area, it is a good idea to make a list of all the weather services available and place it near the chart table. The almanac is a good source of this information, but it is not always easy to find it. Page 27 of the Training Almanac has some weather services listed, with their times and frequencies.

In addition to these, a Navtext receiver can be invaluable when abroad. The broadcasts are printed out in English and they have a greater range than VHF radio being receivable out to about 150 miles offshore.

Even cruising in Southern Ireland , I found the navtext service valuable, for the first week I was there, I could not understand the accents on the radio, and I did not know the locations of the headlands they gave as the limits of the different forecasts. Seeing this information printed out meant I could spend time finding the area concerned!

Customs and paperwork

Travelling from one country to another by yacht, in the European Union is very simple. Provided the crew are EU citizens and you are not carrying prohibited goods you are essentially free to come and go as you wish. But you may still be asked to show your passports.

The Channel Islands and the Canary Islands are not part of the EU and when visiting these places it is necessary to obtain and complete a customs form. These can come directly from a customs officer (if you can find one!) or most marinas on the south coast hold stocks of them. When completed with the details of the crew, destination and return date, this form can be posted in one of the blue Customs and Excise boxes found in most yachting harbours.

On returning from a non-EU country, it is necessary to contact the customs and give the details of your voyage. In practice, the numbers listed in the Almanac are for answer-phones, and it is very unusual to speak to a person.

Flags

On arrival from a non-EU country (including the Channel Islands), a vessel should fly a yellow 'Q' flag until cleared by a customs officer.

should fly a yellow 'Q' flag until cleared by a customs officer.

When arriving in a non-EU country, a 'Q' flag should be flown, until customs formalities have been completed. This applies when travelling from one Channel Island to another. In most countries it is a requirement to arrive at specific harbours to clear Customs.

When in a foreign country, a vessel should display a courtesy flag on the starboard signal hoist. A courtesy flag, is a small version of the countries national flag.

Other papers

For a vessel to travel abroad it must be registered, either as a British Ship or on the Small Craft Register, and the registration documents carried.

Evidence of the vessel's insurance and VAT status may be requested in some countries.

Passports

Even in EU countries, passports should be carried be everyone.

Qualifications

There are many debates about required qualifications. In most cases, they are only compulsory if you visit inland waterways. However, if you have skippering or radio qualifications, it is prudent to carry them when abroad. An International Certificate of Competence is usually sufficient for most purposes, even for a qualified Yachtmaster; it is worth obtaining this certificate.

Up to date details concerning all of the above, especially regarding specific countries can be obtained from the RYA.

RYA House, Romsey Road, Eastleigh, Hampshire, SO50 9YA.

02380 627400

![]() The Routelist.co.uk website has Passage Planning Apps that you may find useful.

The Routelist.co.uk website has Passage Planning Apps that you may find useful.

Additional Resources: